Hackmethod July 2017 — Challenges Write Up

July brings another set of challenges from the Hackmethod team — https://hackmethod.com. This month’s challenge set includes 3 levels and is named “Jam_Packed”. I assumed based off the name that the challenges would be dealing with archives, steganography, or a combination of both. After getting the challenges and reviewing the rules it seems my assumptions were not that far off.

Here is what you can expect to see during this Month's Challenge:

- Packet Analysis

- Forensics

- These will range from beginner to advanced

Available Tools:

- None

- July's challenge will be the 'download and analyze' type using your own tools

Challenge 1 — Pcap: WTF is this!?

What the crap!? What kind of pcap data is this?

We need your help to figure out what’s going on here.

The first challenge for the month pertains to a mysterious .pcap packet capture file. The packet analyzation tool Wireshark is used to load up this capture so we can check each packet and see what type of content we’re dealing with.

USB capture in Wireshark

USB capture in Wireshark

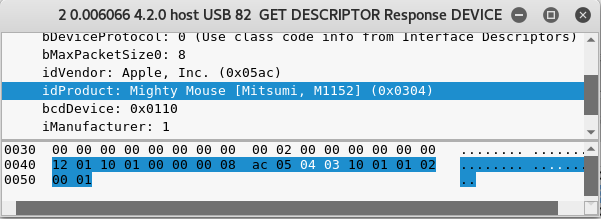

So this packet capture appears to be dealing with USB communication as opposed to standard TCP/UDP traffic. Enumerating through the capture I can see that this communication stream appears to be back and forth to an Apple USB Mighty Mouse.

Getting the idVendor and idProduct values

Getting the idVendor and idProduct values

After researching more about USB packet encapsulation and capture data, I found that the mouse coordinates can be stored as Leftover Capture Data. There was data present in the packet capture, so it was time to look at and extract the data to see what could be gained. A Wireshark filter is applied to filter only the packets containing Leftover Capture Data.

((usb.transfer_type == 0x01) && (frame.len == 70)) && !(usb.capdata == 00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00)

According to reference documentation, the mouse stores it’s X and Y cursor position in bytes 2 and 3. This is shown in the strings below in the Leftover Capture Data column.

Finding the field that stores the mouse X and Y position

Finding the field that stores the mouse X and Y position

Using the tshark tool and the Wireshark filter used above, the Leftover Capture Data values can be extracted from the capture file for further analysis.

tshark -r ~/hackmethod/july2017/wtf.pcap -Y “((usb.transfer_type == 0x01) && (frame.len == 70)) && !(usb.capdata == 00:00:00:00:00:00:00:00)” -e “usb.capdata” -Tfields > stripped.txt

Running tshark and extracting the values

Running tshark and extracting the values

The information in bytes 2 and 3 does appear to be changing through out the capture. Gawk is used to extract the values in bytes 2 and 3, translate the values to coordinates, and then map them into a new file for analysis.

gawk -F: ‘function comp(v){if(v>127)v-=256;return v}{x+=comp(strtonum(“0x”$2));y+=comp(strtonum(“0x”$3))}$1==”01"{print x,y}’ stripped.txt > coords.txt

Translating the values to coordinates with a Gawk one liner

Translating the values to coordinates with a Gawk one liner

Visually mapping the coordinates should now “replay” the mouse cursor movements. This could show input on virtual keyboards, solutions to visual captchas, creating map cursor hot spots, or any other type of recreation for information and forensic gathering. The gnuplot tool is called upon to help plot the coordinates in a visual way.

Using gnuplot to graph the coordinates

Using gnuplot to graph the coordinates

The coordinates are plotted, and the mouse movements draw a picture. Some touch up is then done to the image (mirror flip), and it shows that the mouse was drawing text. The flag Forget_Regular_Pcaps!!has been captured.

Showing the recreated mouse movements and capturing the flag

Showing the recreated mouse movements and capturing the flag

Challenge 2 — Zippity doo dah 2

With the outrage that was zippity doo dah 1 last month, we thought “Why not, let’s try it again…” Help us extract flag.txt and we will give you some cool internet points. #blessed? =D

Last’s month challenges included a corrupt zip file that needed to be fixed and extracted. This month’s challenge takes that task and changes things around a bit. A zip file is provided to all challenge participants which seems to contain the flag. Unzipping the file outputs a wave file, but not the flag.txt file we are looking for.

Unzipping the file

Unzipping the file

Last month the zip **command with the **-FFv switch seemed to fix corrupt zip files well, so it’s time to try it again. Why not use what worked prior? Unfortunately the command fails and does not fix the file. The good news is that it does see that flag.txt is contained in the archive. The location has been confirmed and other methods at extraction can be attempted.

Using ‘zip-FFv‘ to try and fix the zip archive

Using ‘zip-FFv‘ to try and fix the zip archive

One option is to use fuse tools and fuse-zip to see if the zip archive can be mounted as a readable mount point in the file system. The command fuse-zip zippity-doo-dah2.zip zipmount/is ran, mounting the zip file to a Linux directory.

Mounting the zip file with fuse-zip

Mounting the zip file with fuse-zip

In the above screenshot we can see that we have access to flag.txt and out.wav. The cat command is ran on flag.txt, the file content is printed to console, and the flags0Rry-My_Z1pp3r_w4s_d0wnis captured.

Capturing the flag

Capturing the flag

Challenge 3 — Sandstorm

Flash back to 1999 when Darude released this epic track! Wait a second… this version doesn’t sound right. It doesn’t have as much hype as the original.

This challenge was tough. It was tough in that there were multiple hurdles to get over if one was not skilled in a particular topic. At the end of challenge 2 we find out the zip archive contains a wav audio file called out.wav. Wav files in challenges like these generally have a secondary stream of data, audio, or images present in a hidden location. It was now time to find that hidden data.

Using all the usual steganography tools like steghide **and **LSB (Least Signifigant Bit) scripts to extract hidden data in audio seemed to fail. Listening to the wav file produced a half speed version of Sandstorm by Darude. It was time to put on the audio engineer hat and start figuring this out.

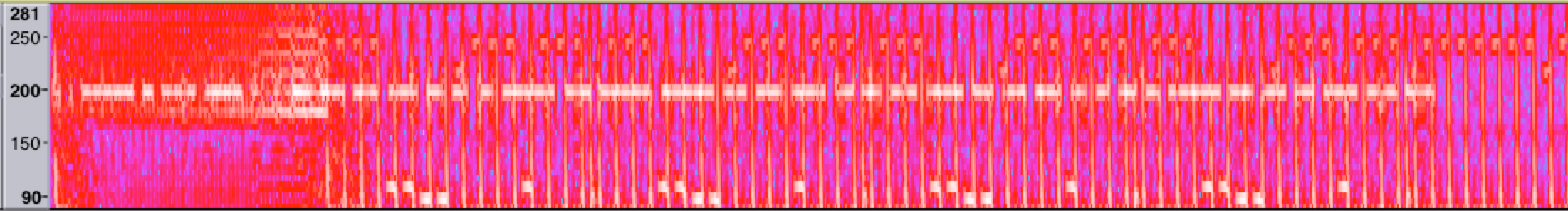

The wav file was loaded in Audacity and it’s sample rate was shown to be 44100 Hz. Based of the clue of the song “not having enough hype” and the fact that it was half speed indicated the sample rate needed to be changed. The sample was updated to 88200 Hz, now at normal speed, and then looked at from a wave form and spectrogram view.

Manually combing through different variations on the spectrogram settings, it seemed that there was some data in the song around 200 Hz that ran for about 35 seconds and then never repeated. Knowing the structure of the song Sandstorm I know that there’s a lot of repeating parts and drum loops, and this can be seen in the spectrogram. The data around 200 Hz seems suspect, so it’s isolated using different high pass filters, low pass filters, and nyquist prompt scripts.

The dashes at around 200 Hz are only present for the first 35 seconds or so of the song

The dashes at around 200 Hz are only present for the first 35 seconds or so of the song

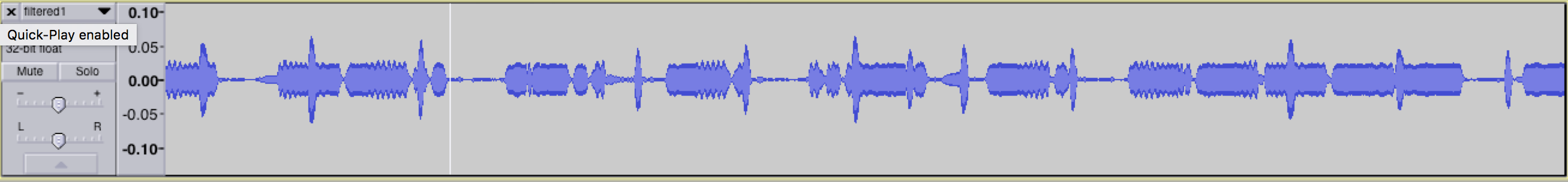

Once the frequency range around 200 Hz is isolated, it’s easier to see the data itself. Viewing the extracted wave form now shows a pattern of slow beeps and long beeps. This seems to be morse code.

A zoomed in wave form in Audacity showing morse code dashes and dots

A zoomed in wave form in Audacity showing morse code dashes and dots

An attempt is made using the remove clicks plugin in Audacity, but in this challenge I had a hard time cleaning up the audio enough to just get the pure morse beeps. The song would either bleed through too much, or drums and clicks would prevent a positive identification on the spectrogram. This was particularly bad in the first 12 seconds and build up portion of the song. I’m sure that if I had experience as a radio technician and/or sound engineer the process would have been easier.

Using visualization tools to more easily identify dashes and dots

Using visualization tools to more easily identify dashes and dots

Eventually through a variety of methods including manual transcription, audio decoders, spectrogram filters and settings, and additional audio visualization programs, a clue is hit as to the contents of the message. It seems the morse code ends in -…- -…- which translates to ==. Strings ending in == are usually base64 encoded, and can be decoded to clear text output.

The morse code is translated to SE0TQ2HHBGX7RDR0X00WCJVLX2MWZDNFN0GWFQ==

The morse code transcribed and decoded

The morse code transcribed and decoded

One thing to note is that the above translation table of the morse code shows the correct case for the base64 string. Originally the transcription from the morse code was only using capital letters, which can cause decoding issues with base64 as it uses both upper and lower case characters. In order to find the correct case I used a variety of methods including python scripts and brute forcing the caps variants by hand for readable output.

The final correctly cased base64 string is:

SE0tQ2hhbGx7RDR0X00wcjVlX2MwZDNfN0gwfQ==

which decodes to the final flag:

D4t_M0r5e_c0d3_7H0

base64 decoding the string and getting the flag

base64 decoding the string and getting the flag

Note This content was originally posted at https://medium.com/@forwardsecrecy/hackmethod-july-2017-challenges-write-up-1303f414c8d6 and is being re-hosted here for archival purposes.