OverTheWire Advent Bonanza 2019

This write up is a culmination of articles from a Capture The Flag competition and are all being concatenated here. You can see other challenge write ups on the main post here.

Easter Egg 1

Part of the fun of CTF challenges is searching for Easter Egg flags. These flags usually don’t require a ton of advanced skill, but are random fun things to find for points during an intense competition.

The only hint for Easter Egg 1 in the OverTheWire Advent Bonanza 2019 was:

TODO: make clean

Last year’s Easter Egg challenge revolved around the robots.txt **file. **Robots.txt does what it’s named for, and provides directions to web site crawlers and spiders (such as Google), as to what files it should and should not index. The challenge last year included the flag inside this file, just in case any end users or curious hackers looked at it’s contents. This year seemed a bit different though.

No dice. The clue TODO: make clean **refers to the C/C++ **make **command. Adding **clean to this command tells the compiler to clean up any old temporary files and artifacts used during the build process. Using that knowledge, we can look for various types of these files on the web server. Eventually, we hit on robots.txt~, which indicates a temporary version of the robots.txtfile.

Finding the secret URL in the temporary robots.txt~ file

Finding the secret URL in the temporary robots.txt~ file

We can see from above, that there is a secret file named /static/_m0r3_s3cret.txt on the web server. Navigating to that file gives us the final flag, and the easter egg has been found.

Sweet easter egg points!

Sweet easter egg points!

Easter Egg 2

Part of the fun of CTF challenges is searching for Easter Egg flags. These flags usually don’t require a ton of advanced skill, but are random fun things to find for points during an intense competition.

Easter Egg 2 gave no hints what-so-ever, except for that fact that it was hosted somewhere on the official OverTheWire Advent Bonanza 2019 website. This would be a search for a needle in haystack (or a flag on a website).

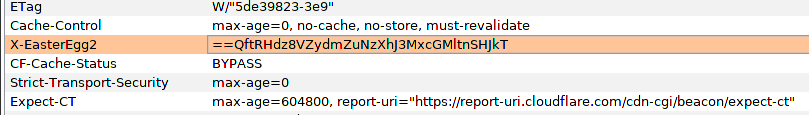

After a bunch of enumeration, a man in the middle web request proxy was used to intercept the web traffic between the web browser and the web server. By doing this, one can see every bit of information that is being sent when a user requests or sends information to a website.

A new an interesting web header was located using the MITM proxy.

Oooooh

Oooooh

The string above should be recognized as base64, but it seems like it’s reversed. Reversing the text and decoding the base64 string gives the following:

Not the final flag, but we can still work with this

Not the final flag, but we can still work with this

Decoding the string does not reveal the final flag, but we do get text we can analyze and work with further. ROT13 is a substitution cipher that literally moves letters forward or backwards a set number of positions, in this case 13 characters. An example of this would be the letter N in a message being written as the letter A (N to A is 13 letters). Using some linux command line fu, we can pipe the text into the tr command and reveal the final flag.

ROT13 decrypt for the final flag

ROT13 decrypt for the final flag

Easter Egg 3

Easter Egg 3 directed competitors to the OverTheWireCTF Twitter page located at https://twitter.com/OverTheWireCTF. One thing that jumped out was a post with a picture signifying a new day in the competition.

Do you see what I see?

Do you see what I see?

The above image actually has a ton of information in it. On first glance, we can see a QR code in the middle of the Egg wearing the Santa hat. Scanning the QR code may yield different results depending on the end user and the application. Here’s why.

Everyone is used to a few types of barcode formats such as QR, PDF417 (on the back of US licenses), and UPC/EAN for products they purchase.

Most people are used to scanning a single type of code and getting the information they need. The above challenge is interesting in that the image pictured contains both a QR code, AND an Aztec formatted code (right in the middle of the picture). If we look back at the original image on Twitter, we can see that the font used in “DAY 10” appears to be Aztec in nature…oh well, let’s scan some codes!

Scan Results

Aztec: 414f54577b6234726330643373

QR Code: 137:64:137:154:171:146:63:175

The numbers in the Aztec code portion correspond to ASCII characters in Hex notation. An example of this would be 41 representing the letter “A”. Decoding this section gives us the first part of the final flag.

AOTW{b4rc0d3s

The numbers above in the QR code portion correspond to ASCII characters in Octal notation. For example, the number 137 represents the character “_”. Decoding this section gives us the second part of the final flag.

_4_lyf3}

Combining both parts yields us the completed and final flag.

AOTW{b4rc0d3s_4_lyf3}

Challenge Zero

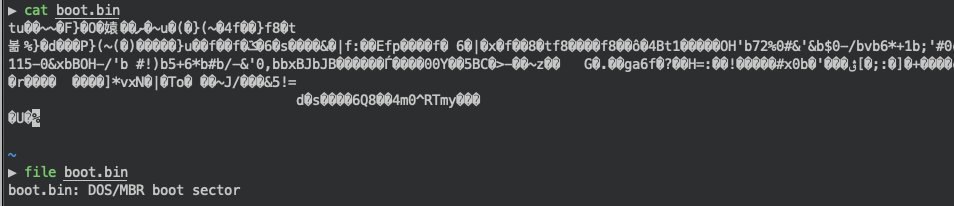

Prior to the start of OverTheWire Advent Bonanza 2019, the creators released a “Challenge Zero” for teams to work on. The challenge was located at https://advent2019.overthewire.org/challenge-zero, which showed a web page with an animated GIF of fire burning with the following message:

Fox! Fox! Burning bright! In the forests of the night!

Hint: $ break *0x7c00

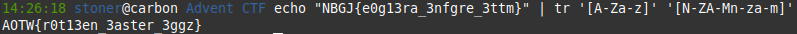

The above hint refers to the command line of gdb, a linux debugger. At this point though, we have nothing to break so we need to keep looking. In the spirit of Capture The Flag competitions, my team and I tried viewing the web page and GIF in different ways. Using the text based browser links leads us to our next clue.

The line “D0NT PU5H M3 C0Z 1M C1053 TO T3H 3DG3” is l33tspeak for a song lyric from The Message by GrandMaster Flash.

The next lyric in the song “I’m trying not to lose my HEAD” clues us in that we need to make a HEAD web request. We can use curl and the command line to easily do this.

Animated Texty Goodness

Animated Texty Goodness

We can see in the above image that the flames are made up of random text characters to achieve the animation effect. The other hint we saw above was “If only the flames wouldn’t move so much” which alludes to the fact that the image is an animation made up of multiple frames. Since we are using curl on the command line, we can scroll back through our console buffer and see each frame of text making up the animation. I noticed that the string of text ended in “==”, which signifies base64 encoding. **By compiling all the text and removing padding characters (# in this case), we get a completed **base64 string.

Base64 decoding the string resulting in a new uuencoded file to play with

Base64 decoding the string resulting in a new uuencoded file to play with

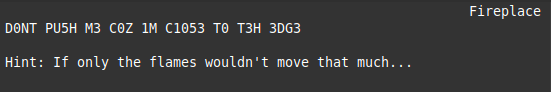

The output above is uuencoded and can be decoded using the xxd tool. Once decoded, we have a boot.bin file. To my surprise, the base64 string did not contain the flag itself, but rather a bootable virtual machine image.

Confirming the file type of boot.bin

Confirming the file type of boot.bin

Taking the binary boot file and loading it into a virtualization hypervisor resulted in the following:

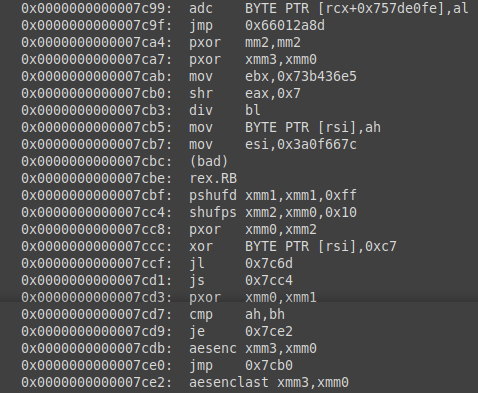

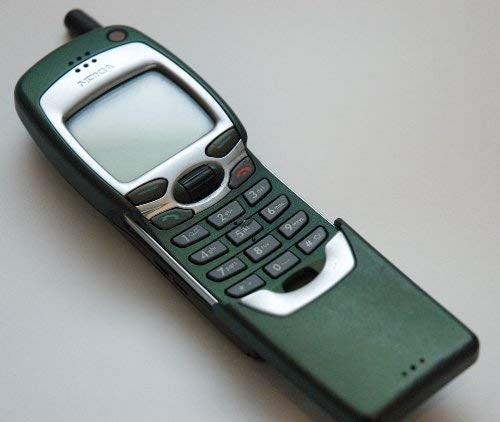

Aha! We have a binary that is loaded and referencing last year’s CTF challenge using the RC4 stream cipher. It seems we need to break this binary as well. Thankfully, the linux command line debugging tool gdb can connect to remotely running binaries for remote debugging purposes. Our original hint of break *0x7c00 finally comes into play. We can now load up gdb, set the proper breakpoint, and start attacking the binary.

Using gdb allows us to dump the Intel formatted assembly code so we can get a better understand of what is going on.

A sampling of the dumped code

A sampling of the dumped code

We can see from the code that we are performing some AES encryption functions of data in the registers. I also noticed that there was a condition to check if the input was 16 characters or not. If it wasn’t, a different jump and code routine was executed. When a password of 16 characters is used, a new jump is taken which performs some XOR operations on the code and various registers.

The program ultimately takes the users input and stores it into xmm3. The instruction at 0x7c62: movaps xmm0,XMMWORD PTR [rsi] moves the AES encryption key into xmm0.

Storing the user input into xmm3

Storing the user input into xmm3

The key is loaded into xmm0

The key is loaded into xmm0

The data in xmm3 then gets XOR’d against a static address which contains hard coded cipher text to see if it matches. If it does, we get the flag. If it does not, the program cleans up the registers and prompts the user again for a password. When we check the debug output we can find the hard coded location and it’s data.

The location of the hard coded cipher text

The location of the hard coded cipher text

The cipher text contents in little endian format

The cipher text contents in little endian format

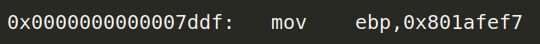

Taking both the cipher text and key allows us to perform an AES decryption which reveals the password we need — MiLiT4RyGr4d3MbR.

Running the script and decrypting the password

Running the script and decrypting the password

At this point we can input the password into the virtual machine, pass the check, and receive the final flag. We went from an animated gif, to base64 text, to a uuencoded boot image, to a binary that needed to be remotely debugged. What a challenge!

7110

Santa is stranded on the Christmas Islands and is desperately trying to reach his trusty companion via cellphone. We’ve bugged the device with a primitive keylogger and have been able to decode some of the SMS, but couldn’t make much sense of the last one. Can you give us a hand?

The Data

The challenge included an archive consisting of 4 comma delimited files, and 3 text files so that competitors could compare the data to the expected result. It was up to us to figure out message #4. Since I’ve been around awhile, I immediately recognized the name and nature of this type of challenge.

The Background

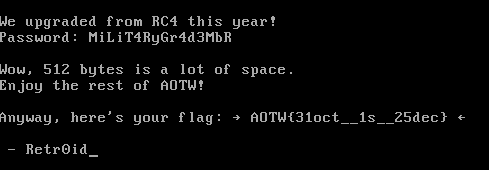

In the pre-smartphone days, Nokia ruled the land of cell phones. They had limited features, could play Snake, and were built like tanks. Before we were all able to touch our screens to make things happen, we needed to use physical hardware buttons. Insane, right?!

Those same hardware buttons were used for sending SMS text messages between phones. Since you were only limited to the buttons on the keypad, each button needed to provide multiple functions.

In order to type the letter A, a user would hit the number 2 button one time. If you wanted to type a B, you’d hit the number 2 button two times. If you wanted a C, you’d hit it three times. This input style was referred to as **Multi-tap **— https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multi-tap.

Now imagine having to type a long story or grocery list to someone using that input style. Thankfully those days of painful texting are over, but this challenge reached out to the old school phreaker inside me.

Nokia 7110

Nokia 7110

In regards to the challenge name, the Nokia 7110 was a special edition phone with a sliding cover in honor of the movie “The Matrix”. The model number itself doesn’t have much to do with the challenge itself, but does point us to the text character set we should be using for the challenge.

The Solution

The 4th message file contained data in the same format as the other files. When looking at the format, it shows a timestamp in the first column, with the digit pressed on the phone in the second. Numbers in the second column appearing in sequence indicate that specific button being pressed multiple times (in order for the letters for that number to cycle).

A sample of csv4 data — the first column is a timestamp/uid and the second is the number pressed

A sample of csv4 data — the first column is a timestamp/uid and the second is the number pressed

You may notice the numbers 100 through 103 and 11 in the above data. These represent the hash, MENU_LEFT, MENU_RIGHT, and other navigation buttons. At this point, the numbered key presses can be extracted and decoded for the flag. Due to the nature and knowledge of multi-tap, this can be achieved manually by hand, or using an automated script such as a python custom dictionary.

The extracted key presses:

100 100 100 100 11 11 2 5 5 5 7 7 7 4 4 4 4 4 4 8 0 7 2 5 5 5 0 4 4 3 3 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 102 3 3 103 0 9 9 9 3 3 0 3 3 3 5 5 5 2 4 0 4 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 3 0 5 5 5 8 8 2 2 2 5 0 3 3 6 6 8 3 3 7 7 7 102 102 102 102 102 102 102 103 101 5 5 103 103 103 103 103 103 4 4 4 6 6 4 0 4 4 4 8 0 9 4 4 4 8 4 4 0 8 4 4 6 6 6 7 7 7 7 3 3 0 4 4 6 6 6 6 6 6 8 8 8 3 3 7 7 7 7 0 5 5 5 6 6 6 5 5 5 0 4 4 4 8 7 7 7 7 0 2 6 6 6 8 9 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 5 5 5 3 3 3 3 8 7 7 7 7 10 10 10 10 3 7 7 7 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 6 6 5 5 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 7 7 7 7 0 0 6 3 3 3 3 10 10 10 10 3 3 4 4 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 4 101 101 0 0 4 10 10 10 10 9 9 9 0 0 8 8 10 10 10 10 2 2 2 7 7 7 4 4 4 4 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 10 10 10 10 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 7 7 7 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 100 100 0 0 6 1 1 0 1 5 5 5 0 1 1 7 100

The Multi-tap decoded output and final flag:

MENU_LEFT MENU_LEFT MENU_LEFT MENU_LEFT HASH HASH [a][l][r][i][g][h][t][ ][p][a][l][ ][h][e][r][s] MENU_UP [e] MENU_DOWN [ ][y][e][ ][f][l][a][g][ ][g][o][o][d][ ][l][u][c][j][ ][e][n][t][e][r] MENU_UP MENU_UP MENU_UP MENU_UP MENU_UP MENU_UP MENU_UP MENU_DOWN MENU_RIGHT [k] MENU_DOWN MENU_DOWN MENU_DOWN MENU_DOWN MENU_DOWN MENU_DOWN [i][n][g][ ][i][t][ ][w][i][t][h][ ][t][h][o][s][e][ ][h][o][o][v][e][s][ ][l][o][l][ ][i][t][s][ ][a][o][t][w][{][l][3][t][s][][d][r][1][n][k][][s][0][m][3][][e][g][g][n][o][g] MENU_RIGHT MENU_RIGHT [0][g][][y][0][u][][c][r][4][z][y][][d][3][3][r][}] MENU_LEFT MENU_LEFT [0][m][.][.][ ][.][l][ ][,][p] MENU_LEFT

Mooo

‘Moo may represent an idea, but only the cow knows.’ — Mason Cooley

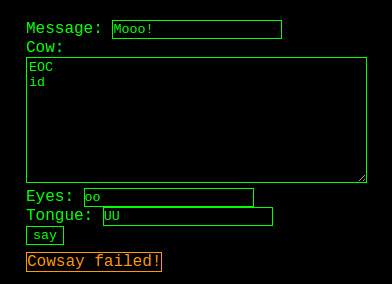

Mooo was one of the more fun challenges and provided us with a web service running on a specific port and IP address. Navigating to the site brings us to an implementation of cowsay. Cowsay takes input from a user and displays it in an ASCII art formatted cow.

The cowsay program (banner at bottom is cut off)

The cowsay program (banner at bottom is cut off)

We know the name of the program due to the banner at the very bottom of the page (not shown here) listing the program version as Powered by cowsay 3.03+dfsg2–4. As a hacker, if we can get access to the source code then we can start looking at places to poke and prod. Cowsay happens to have it’s source code listed at https://github.com/schacon/cowsay/blob/master/cowsay.

Part of the cowsay source code

Part of the cowsay source code

The Solution

After reviewing the Github and source code, we know that cowsay is written in the Perl programming language. Unfortunately, the only input field we’ve seen so far places text in the cow’s speech bubble. Attacking this did not seem to yield any results, as it seems the input field is being sanitized. We need to look elsewhere for an attack vector. Fortunately, a “custom” cow template exists that gives us more input fields to play with.

The custom cow template

The custom cow template

We now know that the program is written in Perl, and we have more input fields to play with. No attacks were found after trying some web application and string escapes in the Message, Eyes, and Tongue field, but something interesting was found when testing things against the Cow text field.

Perl is not one of my strongest or favorite programming languages. Someone on my team decided to RTFM and found a gem inside the Perl documentation located at https://perldoc.perl.org/perlop.html.

The key to the kingdom, and a great Perl escape

The key to the kingdom, and a great Perl escape

They noticed that some Perl scripts contained EOF (End of File), while this one had EOC (I’m assuming End of Command, but it’s actually End of Cow), indicating that the code was to exit after finishing it’s code processing. This EOC command was also present in the custom cow template. We tried to pass EOC, which seemed to work without reporting any errors. After that, we tried chaining commands with the linux id command to see if we had escaped Perl and reached a shell.

Cowsay failed, but have we?

Cowsay failed, but have we?

The server didn’t like our id command, so it didn’t seem we were at a shell yet. We did get an error message when adding the id command, whereas we did not when previously trying just EOC, so it seems we’ve escaped Perl, but now we’re….somewhere else entirely.

No, not there.

No, not there.

Knowing that web applications can only be hosted by a variety of services, we try a variety of commands in different syntax. When attempting a python module import, we no longer receive any errors.

No errors!

No errors!

Did we escape from Perl and land in Python? I think we did! Let’s see if we can get python to execute shell commands for us using the os.system call.

The final flag

The final flag

The python call executes and we get the final flag. Mooo!

Tiny Runes

One of Santa’s Little Helpers received an unusual Christmas wish, a copy of the yet to be released Deus Hex game. All they managed to find were fragments from the dialogue system. Can you decode the last one?

The Data

The “tiny runes” challenge was a reverse engineering and forensics challenge that included an archive containing 4 binary files containing speech text data for a game engine. Files 1 through 3 included a .txt file showing the game text, so that competitors would have examples to reference. The goal was to take the binary data for the fourth file, and come up with the corresponding text (hopefully containing the flag).

An example of provided game engine text

An example of provided game engine text

Contents of the binary file

Contents of the binary file

While we didn’t see anything in the binary files using things like strings, the real magic was looking at the hex data (per the game name in the clue) of the file in order to see what bytes were being read.

A hex dump of the example binary file #1

A hex dump of the example binary file #1

All 4 provided binary files had mostly the same bytes and format, up until the section starting at 0x329. Since the data was different between all 4 files, it was determined that this was where the speech text data was being stored.

Each file had the values 00 00 00 XX **in **0x329 to 0x3BF, with the last byte seeming to indicate the size of the text about to follow.

We know from the 1st binary file and text that the line starts off with “JC Denton”, but the next bytes we are looking at currently show 05 01. How does this map to the letter “J”?

Binwalking for more

Binwalking for more

Running the binwalk or foremost forensic tools on the binary files not only shows text data, but we see a PNG image file that we can carve out and extract. The image file itself appears to be a character legend, showing a different arrangement of game text characters.

The extracted PNG file.

The extracted PNG file.

The Solution

Remember we were trying to figure out how to get the next bytes in the binary file, 05 and 01, to represent the character “J”? From the above legend, if we count starting from 0 from the top down, left to right — “J” is 01 row down, and 05 characters over. Remember to start counting from 0. “C” would be 03 across, and 0A rows down. It seems the text is being encoded in the file using a grid pattern with coordinates to which character is which.

Using this, we can reverse engineer the 3 provided binary and text files to generate our own character mapping so that we can process the 4th binary file, and get the final text.

Checking the bytes for the 4th binary

Checking the bytes for the 4th binary

The bytes from 0x399 to 0x3D8 contain our flag string.

07 04 04 05 04 0A 04 09 01 09 00 06 00 09 05 03 00 0A 02 02 05 03 02 02 07 03 02 00 00 0A 00 0A 01 05 00 05 02 02 06 02 01 04 03 08 01 05 02 02 06 02 02 00 07 03 04 02 05 03 00 0A 07 09 06 07

Using the legend above, we can start working through the byte pairs/coordinates by hand, or use an automated script. 07 across and 04 down would be the character “A”. 04 across and 05 down would be the character “O”, and so on and so on until we get the final flag — AOTW{wh4t_4_r0tt3n_fi13_f0rm4t}.

Santa’s Signature

Can you forge Santa’s signature?

The Data

We are provided a remote service to connect to, as well as some source code on how that service is running.

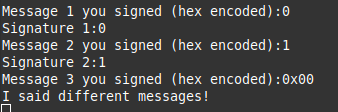

The remote service

The remote service

The remote service (and reading the source code) shows us a generated textbook RSA public key, and a request for us to provide 3 signed messages and digital signatures in hex encoding. Generally during CTF competitions, RSA challenges come down to factoring an unknown private key in order to decode a message. This is due to the fact that textbook RSA does not contain any padding, and can be defeated using cryptography and algebra.

Textbook RSA

Textbook RSA

In order to crack the private key, we need a modulus (n) and exponent (e) that conform to certain properties (small modulus, small exponent, similar modulus/exponent)so that it’s easier to defeat the cryptography and math.

When checking these values, it seems we cannot crack the private key itself in this challenge due to such a large modulus (n) value.

n = 0xbb58dbdfd1999…[lots of characters]…d64f501c6640b95c57f e = 65537

Based off the source code for the remote service, we need to pass 3 messages and provide 3 valid digital signatures per the key.verify(m,s) *check.*

Since we can provide the message and digital signature, there is an easy way to trick this automated verification system into accepting forged signatures. If we use the values of 0 for the message and signature, or the values of 1 for both — the RSA signature formula (s^e mod n) should still calculate out and pass all the requested checks.

Passing check 1 and 2, but not check 3.

Passing check 1 and 2, but not check 3.

We were able to pass message 1 and message 2 by using the values 0 **and **1, but we can’t provide either of those again for the 3rd message. Bummer.

But wait…we know the modulus (n), the exponent (e), and we can control the digital signature (s). Using this, we can figure out an appropriate message (m) that should pass verification from a set digital signature.

Since this is an automated system, our message does not need to be human readable — it only needs to pass the signature verification check. Running the script above outputs a hex string that we can input as the message, and a digital signature of 0xf.

This passes the third check, and we can see the final flag.

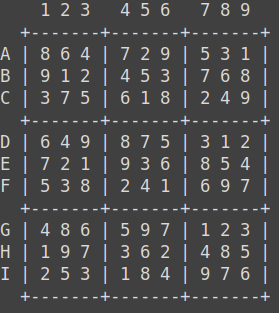

Sudo Suduko

The Challenge

Santa’s little helpers are notoriously good at solving Sudoku puzzles. Because regular Sudoku puzzles are too trivial, they have invented a variant.

The Sudoko puzzle to solve

The Sudoko puzzle to solve

In addition to the standard Sudoku puzzle above, the following equations must also hold:

B9 + B8 + C1 + H4 + H4 = 23 A5 + D7 + I5 + G8 + B3 + A5 = 19 I2 + I3 + F2 + E9 = 15 I7 + H8 + C2 + D9 = 26 I6 + A5 + I3 + B8 + C3 = 20 I7 + D9 + B6 + A8 + A3 + C4 = 27 C7 + H9 + I7 + B2 + H8 + G3 = 31 D3 + I8 + A4 + I6 = 27 F5 + B8 + F8 + I7 + F1 = 33 A2 + A8 + D7 + E4 = 21 C1 + I4 + C2 + I1 + A4 = 20 F8 + C1 + F6 + D3 + B6 = 25

If you then read the numbers clockwise starting from A1 to A9, to I9, to I1 and back to A1, you end up with a number with 32 digits. Enclose that in AOTW{…} to get the flag.

The Solution

This is a tough challenge consisting of math and programming in order to find the flag. One must solve a Sudoku puzzle by finding 32 digits, but the puzzle must also meet a list of very specific conditions. Due to this, only an extremely small subset of Sudoku solutions (in this case, one) will meet the conditions and unlock the final flag.

Enter go programming guru and CTF team member solipsis.

In order to solve a challenge such as this, one must do some paper math and preparation work in order to prune and reduce the search space early on. Since we have a fixed number of already filled out numbers, ranges for the missing inputs could be figured out — which helps reduce the complexity and brute force space search by a few orders of magnitude.

Programming this script to “fail early” as soon as it finds any value that exceeds those in the list of conditions, rather than checking conditions once it has an entire puzzle solution, also helps to speed things up quite a bit.

These techniques, combined with a descending 9 ->1 number order, help to trigger the failure conditions faster, and reduces magnitudes even further.

After running the script for some time, a final Sudoku solution that meets the list of requirements is found.

Success!

Success!

Per the challenge description, the 32 found numbers are compiled into a single string for a final flag of AOTW{86472953189247356794813521457639}.

Note This content was originally posted at https://medium.com/@forwardsecrecy/overthewire-advent-bonanza-2019-capture-the-flag-competition-66c50671c641 and is being re-hosted here for archival purposes.